Classic shunga in praise of shadows

Classic shunga art has influenced my work for a long time. Lately, I have been yearning to return to where my erotic art once began. Over time, I have developed a personal style of painting that bears little resemblance to the classic shunga prints that first kindled my artistic flame.

My current work is more influenced by Japanese painting styles such as nihonga and shin hanga prints. An artist’s evolution is a constant. Perhaps it was nostalgia that made me begin work on a new series of paintings in which I pay tribute to the genre to which I owe so much of my aesthetic foundation.

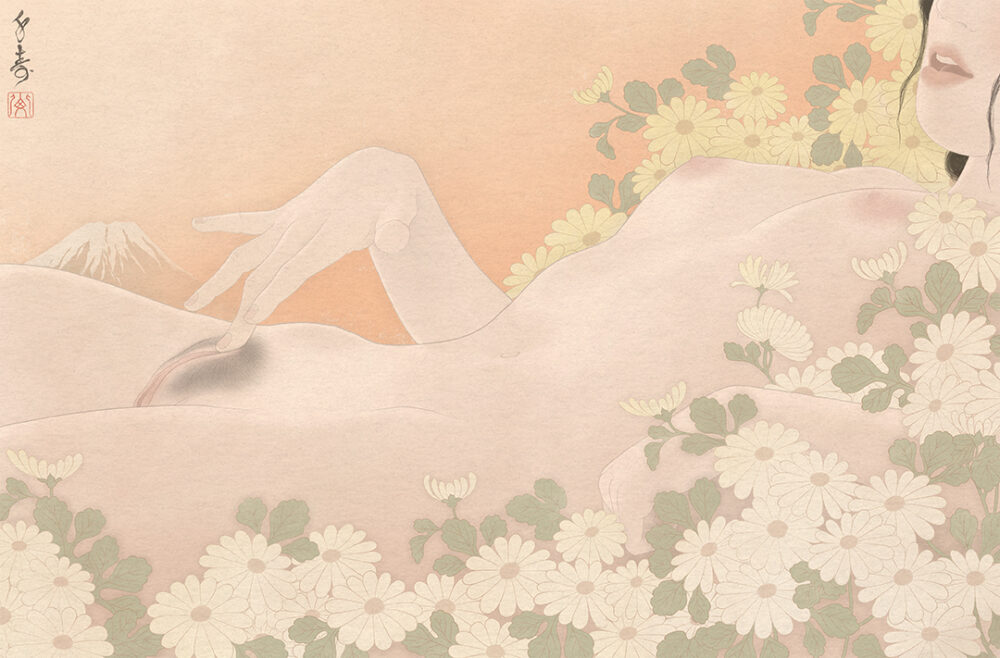

“In Praise of Shadows” by Senju

Through reworking classic shunga art by my favourite Ukiyo-e artists, I hope to learn new skills and gain a deeper understanding. Hopefully, my work will add to the ongoing and ever-evolving tradition of Japanese art. Before I present my new series to you more in-depth, it is perhaps a good idea to quickly discuss the background of this unique genre of erotic art.

Japanese erotic art, shunga (spring pictures) is synonymous with Ukiyo-e. This art form, mainly expressed in woodblock prints, was a revolutionary new genre that emerged in the Edo period (1603-1868). Aimed toward the inhabitants of Japan’s capital Edo ( now Tokyo), Ukiyo-e portrayed Kabuki actors, warriors, landscapes and beautiful women.

Mass-production of woodblock prints using a refined yet complex technique ensured low prices for the consumers. Collecting them soon became a part of Edo life. The popularity of Ukiyo-e remained strong up to the late 1800s when photography replaced woodblock prints.

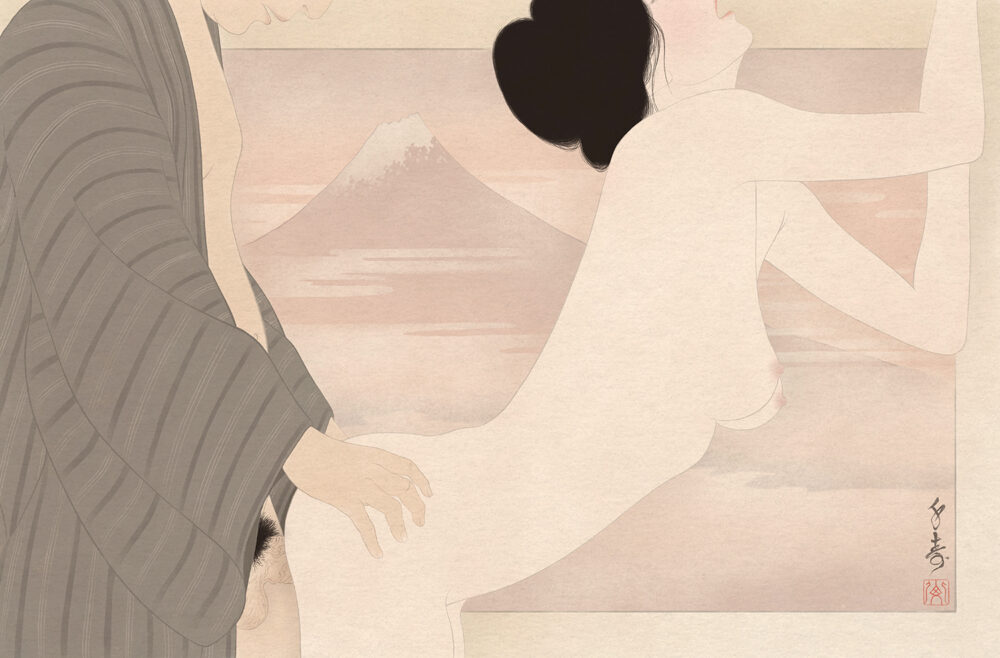

Classic shunga designed by Kikukawa Eizan

In the early 1700s, Edo had grown from a small fishing village into a metropolis. Roughly one million people called Edo home. It was by that time one of the largest cities in the world, of which a large part of the population were men. Artisans, craftsmen and labourers had been flocking to Edo from all corners of Japan to build the Tokugawa shogun’s new capital.

There were roughly five men to every woman, and most of the women in Edo at that time belonged to the samurai class. They were not allowed to fraternise with working men, so a need and subsequent market rose for woodblock-printed illustrated shunga books.

Classic shunga sprang out of a tradition of painted handscrolls depicting erotic scenes. These lavish scrolls had so far only been available to predominantly wealthy men who commissioned them from artists to use for their sexual gratification. However, the cheap printing technique afforded by woodblock printing now made this treasured material available to working men (and women) at a price everyone could afford.

Painted Shunga e-maki (picture scrolls)

Shunga books, as well as single prints, quickly became sought after. The market soared. No Ukiyo-e publishing house worth the name could afford to stay out of the highly lucrative market of pornography.

The same went for the skilled artists designing the prints. Praised and acclaimed artists like Katsushika Hokusai, Utagawa Kuniyoshi and Kitagawa Utamaro were prolific creators of classic shunga.

Shunga e-hon (picture books)

The title of my new series of classic shunga paintings is “In Praise of Shadows (In’ei Raisan)”. The title refers to the wonderful essay by the same name by Japanese author Jun’ichiro Tanizaki.

Tanizaki’s text, published in 1933, reminisces about an old Japan lost a frenzy of modernising.

The author speaks beautifully and lovingly about the bygone days of paper lanterns and candlelight. He vividly describes how the gold leaf on folding screens reflects the naked flame, absorbing the light and then softly disperses it around the room. He talks about how the rich tones of traditional red and black in Japanese lacquerware come alive in dimly lit restaurants and how the soft, insufficient light leaves the corners mysterious and dark.

It is a Japan before the brutality of electric light. A culture of dusk and imagination.

When I light a candle in my very small yet cosy art studio, I can firsthand experience what Tanizaki was trying to say. I have made sure to surround myself with objects that feed my imagination. Noh masks, Obi (kimono sashes) with rich gold embroidery, small folding screens, traditional Kyoto fans used in dances and even a hand made miniature samurai armour make sure I feel at home when creating.

I have collected these over the past 20 years, and even if my tiny studio goes through many transformations each year, these objects remain. In the light of my electric lamp, they are beautiful, interesting objects, but in candlelight, they become portals into a suggestive and fantastic world!

In almost all classic shunga prints it seems as if the persons portrayed are making love in harsh daylight. This is due to Ukiyo-e art depending on the expressiveness of the line rather than a description of light and shadows. In reality, a vast majority of the scenes take place at night.

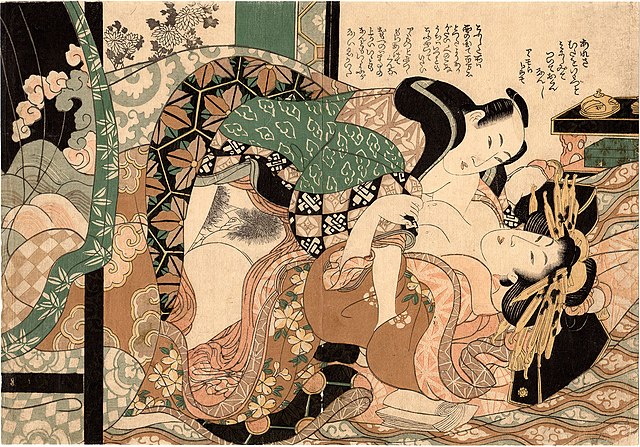

Print no.10 (of 12) from “Utamakura” by Kitagawa Utamaro.

Senju’s nighttime version of Utamaro’s Shunga masterpiece

In late December 2021, I began to understand how to do it. While I was working on another art project, I had accidentally stumbled on technique simply enough to not interfere with the expression of the line. All I had to try it out, experiment and then refine it.

I began with a favourite shunga print by Kitagawa Utamaro. As is common in classic shunga, this piece does not have a title. It’s one out of twelve prints featured in the book “Utamakura (poem(s) of the pillow)”, and is perhaps Utamaro’s most sensual shunga work. The image portrays a couple in a romantic yet explicit scene set in a second-story room of a teahouse. She is a meshimorion’na (a maidservant that also works as a prostitute). This is written on the folding fan, along with a poem by Ishikawa Masamochi that reads:

Hamaguri ni

Hashi o shikka to

Hasamarete

Shigi tachikamuru

Aki no yugure

In English:

Its beak caught firmly

In the clamshell

the snipe cannot

Fly away

Of an autumn evening

The true nature of the relationship between the man and the woman portrayed is hard to figure out. This is a task I will leave to your imagination.

I have tried to create a classic shunga work as faithful to the original as possible. My hand is evident in the linework, also the choice of colours for the woman’s kimono and obi. The paper lantern is not part of Utamaro’s original design, but I will continue to take liberties such as this when continuing this series.

It is my hope to be forgiven by the artist, my audience and history itself.

Kindly, Senju